You walk into a room and detect a damp, earthy, musty scent—something you can’t quite put your finger on. Is that mold? The question “does mold smell?” sounds simple, yet it conceals fascinating complexity. A moldy odor is often one of the first warning signals of fungal growth in buildings, yet the presence or absence of odor doesn’t always tell the entire story.

In this article, I’ll draw on scholarly sources, environmental-health guidelines, and professional remediation experience to explore:

- Why mold can produce odor, and what chemical compounds are responsible

- When smell is a helpful indicator — and when it is unreliable

- The health implications of mold odors and what they tend to signal

- Practical steps for detection, mitigation, and remediation

This deep dive is written for building managers, indoor‑air professionals, facility engineers, environmental health specialists, and other practitioners who need a clear, evidence‑driven understanding of odor as a diagnostic tool. Let’s begin.

Why Does Mold Smell? The Science Behind the Odor

What Are mVOCs (Microbial Volatile Organic Compounds)?

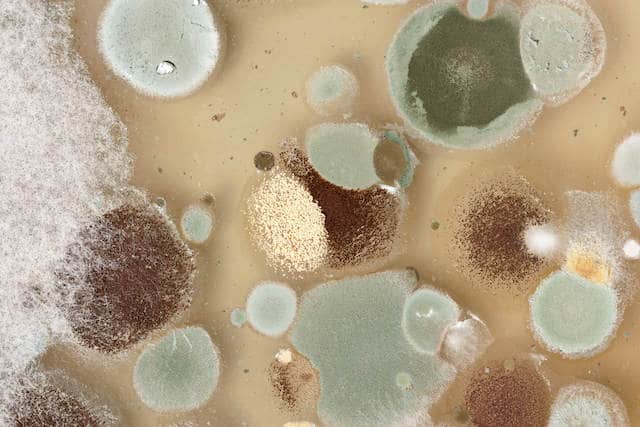

Mold does not inherently carry a fragrance in the way a flower does; rather, the scent commonly described as “moldy” or “musty” comes from metabolic by‑products expelled into the air. These compounds are known as microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs). The U.S. The Environmental Protection Agency notes that some compounds produced by molds have strong smells and are volatile, quickly released into the air — and these are often the source of that moldy odor.

mVOCs include alcohols, ketones, aldehydes, and sulfur‐ or nitrogen‐containing molecules. As mold digests organic material (wood, drywall, paper, dust), it releases these gases. Because they are volatile, even small amounts may diffuse through porous surfaces and be perceived by the nose.

Interestingly, mVOCs are not identical across species. Different fungi produce different profiles of volatile compounds, meaning the exact odor can vary.

Factors That Influence the Smell Profile

Several environmental variables determine how strong the odor is and whether it becomes noticeable:

| Factor | Influence | Notes / Examples |

| Species of mold | Some fungi are particularly pungent (e.g. Stachybotrys “black mold”) | Stachybotrys chartarum is often associated with a stronger, dank smell |

| Growth substrate | What the mold is feeding on (wood, wallpaper, insulation) affects the compounds released | Mold growing on drywall in a bathroom vs wood in a basement may smell differently |

| Extent of biomass | Larger colonies release more mVOCs | A small patch may emit negligible odor |

| Moisture / humidity / temperature | More active growth → more volatile emission | Warm, humid conditions encourage increased metabolic rate |

| Ventilation / airflow | Poor ventilation lets odor concentrate; crossflows can carry odor from hidden areas | HVAC duct leaks may spread a musty smell |

| Age / decay stage | As mold transitions through growth phases, the types (and intensities) of mVOCs can shift | Early growth may smell less than decay or sporulation phases |

Because of this complexity, the same mold species in different settings may smell subtly different—or not smell at all.

Can You Always Smell Mold? When Smell Is (and Isn’t) a Reliable Indicator

Hidden Mold & Smell Attenuation

Many mold infestations are located behind walls, under floors, or inside ductwork where they won’t be directly exposed to air currents. In such cases:

- mVOCs can be absorbed or adsorbed by materials like drywall, insulation, carpets, and upholstery, reducing or muting the scent as it travels to occupied spaces

- Low-intensity growth may not produce enough mVOCs to be perceptible

- Competing odors (cleaning agents, perfumes, furniture off-gassing) may mask or distract from subtle musty scents

Consequently, absence of a smell does not guarantee absence of mold. As one mold remediation guide emphasizes, “you shouldn’t rely solely on your sense of smell to detect mold.” (Mold Busters)

There are documented cases where laboratory air sampling turned up elevated fungal concentrations even when occupants did not perceive an odor. One user noted:

“Lab report spore concentration seems normal, but I can smell it …”

Similarly, in one property scenario, a visitor immediately complained of mold odor and nose irritation, while other occupants didn’t notice anything.

Thus, smell is a useful early-warning tool—but not definitive.

Variation Among Individuals & Sensitivity

Odor perception is subjective. Factors that influence individual sensitivity include:

- Genetic differences in olfactory receptors

- Prior exposure and sensitization (people who have been exposed to mold repeatedly may become more or less sensitive)

- Health status (nasal congestion, allergies, sinus issues)

- Attention and awareness—some people are hyperaware of indoor smells, others less so

Because of this variation, two persons in the same space may report entirely different sensory experiences.

In fact, anecdotal accounts often highlight these discrepancies. One tenant described severe respiratory symptoms and strong perception of mold odor, while another occupant in the same dwelling claimed no smell at all.

Health Implications of Mold Odors & What They Signal

Odors vs Spores: What’s Doing the Harm?

It is important to clarify: the odor itself (mVOCs) is not typically the primary health hazard. Rather, smell is an indicator of fungal activity, and the real risks stem primarily from:

- Spores and aerosolized particulates, which may carry allergens or toxins

- Mycotoxins (in certain species under certain conditions)

- Inflammatory or irritant compounds exposed in close quarters

The EPA notes that the health effects of inhaling mVOCs are largely unknown, though they have been associated with headaches, nasal irritation, dizziness, fatigue, and nausea.

Meanwhile, exposure to molds more broadly is well-documented to produce allergy-like symptoms, asthma exacerbations, and respiratory irritation.

The Centers for Disease Control lists common responses to damp and moldy environments: cough, wheeze, nasal stuffiness, skin irritation, eye irritation, and impairment of lung function in susceptible individuals.

Thus, while detecting a moldy scent doesn’t guarantee immune harm, ignoring that scent is a risky decision—because it signals active fungal growth that may compromise indoor air quality.

Vulnerable Populations & Reported Symptoms

Some individuals are more likely to be affected by mold exposure (and perhaps more likely to notice smells). Key groups include:

- People with asthma or allergies — mold exposure can provoke attacks or aggravate symptoms

- Infants, children, elderly — more sensitive to irritants, less efficient respiratory defenses

- Immune-compromised individuals — may develop fungal infections or heightened inflammatory responses

- Workers in moisture-prone environments — such as HVAC systems, agricultural barns, or basements, especially when exposure is chronic

Documented health results in damp buildings include increased incidence of asthma, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, and upper respiratory tract symptoms even in otherwise healthy individuals.

Given this, the presence of a moldy odor should trigger a proactive investigation and response.

How to Detect, Localize & Confirm Mold When You Smell Mustiness

Systematic Investigation – Start With the Nose

When an occupant reports a mold-like smell, a methodical approach is key:

- Map the odor strength

- Move around and note where the smell is strongest (near walls, floors, ceilings, cabinets)

- Mark approximate odor “hot zones”

- Move around and note where the smell is strongest (near walls, floors, ceilings, cabinets)

- Look for moisture clues

- Condensation, water stains, peeling paint, rusted fasteners

- Leaks in plumbing, roof, windows, HVAC drip pans or condensation lines

- Condensation, water stains, peeling paint, rusted fasteners

- Inspect high-risk rooms first

- Bathrooms, kitchens, basements, attics, laundry areas, behind furniture

- Under sinks, behind appliances, inside ductwork, inside wall cavities

- Bathrooms, kitchens, basements, attics, laundry areas, behind furniture

- Smell test materials

- Press a piece of clean white tissue or cardboard to suspected surfaces (walls, panel joints) for a few minutes, then smell the tested section

- Sometimes this acts like a “mVOCs concentrator”

- Press a piece of clean white tissue or cardboard to suspected surfaces (walls, panel joints) for a few minutes, then smell the tested section

- Use a trained sense of smell

- Professionals often carry odor‐filtering masks so that chronic odors don’t dull their sensitivity

- Avoid wearing strong perfumes or cleaning chemicals during inspection (they may mask subtle odors)

- Professionals often carry odor‐filtering masks so that chronic odors don’t dull their sensitivity

- Ventilate & retest

- Turn off HVAC, isolate the area, then ventilate and re-enter to re‑assess odor. A persistent musty smell suggests the source is not transient.

- Turn off HVAC, isolate the area, then ventilate and re-enter to re‑assess odor. A persistent musty smell suggests the source is not transient.

Taking these steps helps narrow the locale of the odor source before investing in more advanced diagnostics.

Professional Tools & Testing – Pros & Limitations

Once you suspect mold, you may consider employing professional testing or measurements. Common tools include:

- Air sampling (spore traps, impaction samplers)

- Surface swabs or tape lifts

- mVOC detectors / sensors

- Infrared / thermal imaging (to locate moisture zones behind surfaces)

- Relative humidity / dew point mapping

However, each method has limitations:

- There is no universally accepted safe threshold for mold spores or species indoors

- mVOC sensors may detect volatiles, but they cannot reliably identify species or quantify exposure levels in typical building settings

- Air sampling only captures a snapshot; concentrations may fluctuate over time

- Surface tests find localized presence—but may miss spores that are airborne or unreachable

According to CDC guidance, in many cases visual inspection plus odor detection is more useful than testing. The CDC does not recommend routine mold sampling.

Thus, testing can aid decision-making (e.g. before large remediation) but should not replace thorough inspection or practical remediation steps.

Remediation Strategies for Odor & Mold Control

Source Elimination & Moisture Control

Effective mold smell control begins with eliminating what drives fungal growth:

- Fix leaks in roofs, plumbing, windows, foundations

- Improve drainage and site grading to divert water from building base

- Lower indoor humidity (aim for < 50% relative humidity) using HVAC, dehumidifiers, ventilation, and desiccants (CDC)

- Ventilate bathrooms, kitchens, laundry rooms externally

- Seal leaks or gaps in building envelope and ductwork

- Repair condensate lines, insulate cold surfaces prone to dew formation

Without controlling moisture, mold will reappear—and odor will persist.

Cleaning, Containment & Odor Removal

Once the source is broken, next steps focus on removing fungal growth and residual odors:

Cleaning / Removal

- For hard, non-porous surfaces: scrub with detergent, water, or EPA-registered fungicides

- Porous materials (e.g. drywall, ceiling tiles, insulation, carpets) that are heavily contaminated often must be removed and replaced

- Contain the work area with plastic sheeting and negative pressure to avoid spore spread

- Use HEPA-filter vacuums for dust and spore cleanup

Odor absorption / mitigation

- Activated charcoal, baking soda, zeolites placed in affected zones

- Air purifiers with carbon + HEPA filters

- Ozone or hydroxyl generators (used cautiously, professionally)

- Avoid merely masking with sprays; they don’t solve the underlying source

Drying / aeration

- Use fans, dehumidifiers, and heat to dry surfaces fully

- Keep airflow continuous until odor subsides

Many professionals emphasize that odor may linger even after mold removal, because mVOCs may have penetrated materials deeply. In those cases, repeated cleaning, odor scavengers, and time help dissipate residual smell.

When to Call Experts

You should engage professional mold remediation when:

- The affected area is large (e.g. more than 10 square feet or across multiple compartments)

- There is mold in HVAC systems, concealed cavities, or structural elements

- Occupants report serious health symptoms

- You are dealing with sensitive populations (children, immunocompromised, asthma)

- Odor persists despite your cleanup efforts

- Legal or insurance considerations require documentation and validated remediation

Professionals bring containment procedures, industrial-grade equipment, and certified protocols to manage high-risk situations safely.

Conclusion

So, does mold smell? Yes—frequently. The “musty” or “earthy” odor that many people associate with mold often comes from microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs) emitted by active fungal colonies. But that smell is not guaranteed; hidden or low-intensity mold growth may produce little to no odor, and different individuals perceive smells differently.

The smell of mold is not just a nuisance—it’s a diagnostic indicator. While the odor itself is seldom the direct toxic threat, it signals that fungal growth is underway—a process that may release spores, allergens, or toxins capable of harming occupant health. Hence, professionals should treat a moldy scent as a red flag, prompting investigation, inspection, and remediation.

In practice: use a systematic approach (mapping odor, inspecting moisture sources, localizing hotspots), supported as needed by testing, and always aim to eliminate moisture, contain spores, clean surfaces, and mitigate residual odor. Call in experts for complex or high-stakes cases.

Finally: if you walk into a space and detect that unmistakable damp, musty smell, don’t ignore it—but follow the science. Are you ready to apply these steps in your facility or building with confidence?